Notice: this Wiki will be going read only early in 2024 and edits will no longer be possible. Please see: https://gitlab.eclipse.org/eclipsefdn/helpdesk/-/wikis/Wiki-shutdown-plan for the plan.

Difference between revisions of "The Official Eclipse FAQs"

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

=== All about Plug-ins === | === All about Plug-ins === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Part I discussed the Eclipse ecosystem: how to run it, how to use it, and how to extend it. In this chapter, we revisit the topic of plug-ins and lay the groundwork for all plug-in development topics to be discussed in later chapters. This chapter answers questions about the core concepts of the Eclipse kernel, including plug-ins, extension points, fragments, and more. All APIs mentioned in this chapter are found in the org.eclipse.core.runtime plug-in. | ||

:*[[FAQ What is a plug-in?]] | :*[[FAQ What is a plug-in?]] | ||

| Line 173: | Line 175: | ||

=== Runtime Facilities === | === Runtime Facilities === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Above, we already discussed most of the basic functionality of the org.eclipse.core.runtime plug-in. This chapter covers the remaining facilities of Eclipse Platform runtime: APIs for logging, tracing, storing preferences, and other such core functionality. These various services, although not strictly needed by all plug-ins, are common enough that they merit being located directly alongside the Eclipse kernel. In Eclipse 3.0, this plug-in was expanded to add infrastructure for running and managing background operations. This chapter answers some of the questions that may arise when you start to use this new concurrency infrastructure. | ||

:*[[FAQ How do I use progress monitors?]] | :*[[FAQ How do I use progress monitors?]] | ||

| Line 191: | Line 195: | ||

=== Standard Widget Toolkit (SWT) === | === Standard Widget Toolkit (SWT) === | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the great success stories of the Eclipse Platform has been the overwhelming groundswell of support for its windowing toolkit, SWT. This toolkit offers a fast, thin, mostly native alternative to the most common Java UI toolkits, Swing and Abstract Windowing Toolkit (AWT). Religious debates abound over the relative merits of Swing versus SWT, and we take great pains to avoid these debates here. Suffice it to say that SWT generates massive interest and manages to garner as much, if not more, interest as the Eclipse Platform built on top of it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The popularity of SWT has forced us to take a slightly different approach with this chapter. The SWT newsgroup was created in July 2003 and since then has generated an average of 136 messages every day. In this book, we could not even scratch the surface of the information available there. Although we could present the illusion of completeness by answering a couple dozen popular technical questions, we would not be doing the topic justice. Instead, we focus on answering a few of the higher-level questions and providing as many forward pointers as we can to further information on SWT available elsewhere. A benefit of SWT’s popularity is the wealth of Web sites, discussion forums, books, and other forms of documentation out there. Thus, although we won’t be able to answer all SWT questions, we hope at least to steer you to the resources that can. However, a handful of questions are asked so often that we can’t resist answering them here. | ||

:*[[FAQ What is SWT?]] | :*[[FAQ What is SWT?]] | ||

| Line 206: | Line 214: | ||

=== JFace === | === JFace === | ||

| + | |||

| + | JFace is a Java application framework based on SWT. The goal of JFace is to provide a set of reusable components that make it easier to write a Java-based GUI application. Among the components JFace provides are such familiar GUI concepts as wizards, preference pages, actions, and dialogs. These components tend to be the bits and pieces that are integral to the basic widget set but are common enough that there is significant benefit to drawing them together into a reusable framework. Although its heritage is based on a long line of frameworks for writing IDEs, most of JFace is generally useful in a broad range of graphical desktop applications. JFace has a few connections to classes in the Eclipse runtime kernel, but it is fairly straightforward to extract JFace and SWT for use in stand-alone Java applications that are not based on the Eclipse runtime. JFace does not make use of such Eclipse-specific concepts as extensions and extension points. | ||

:*[[FAQ What is a viewer?]] | :*[[FAQ What is a viewer?]] | ||

| Line 228: | Line 238: | ||

:*[[FAQ How do I set the title of a custom dialog?]] | :*[[FAQ How do I set the title of a custom dialog?]] | ||

:*[[FAQ How do I save settings for a dialog or wizard?]] | :*[[FAQ How do I save settings for a dialog or wizard?]] | ||

| − | |||

=== Generic Workbench === | === Generic Workbench === | ||

| + | |||

| + | This chapter covers FAQs relating to the generic workbench and its APIs. Workbench is the term used for the generic Eclipse UI. Originally the UI was called the desktop, but because Eclipse was a platform primarily for tools rather than for stationery, workbench was deemed more suitable. In Eclipse 3.0, tools are no longer the sole focus, so the term Rich Client Platform, is starting to creep in as the term for the generic, non-tool-specific UI. After all, people don’t want to play mine sweeper or send e-mails to Mom from such a prosaically named application as a workbench. A rich client, on the other hand, is always welcome at the dinner table. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many of the important workbench concepts, such as editors, views, and actions, generate enough questions that they deserve their own chapters. This chapter focuses on general questions about integrating your plug-in with the various extension hooks the workbench provides. | ||

:*[[FAQ Pages, parts, sites, windows: What is all this stuff?]] | :*[[FAQ Pages, parts, sites, windows: What is all this stuff?]] | ||

| Line 258: | Line 271: | ||

=== Perspectives and Views === | === Perspectives and Views === | ||

| + | |||

| + | This chapter answers questions about two central concepts in the Eclipse Platform UI. Perspectives define the set of actions and parts that appear in a workbench window and specify the initial size and position of views within that window. Views are the draggable parts that make up the bulk of a workbench window’s contents. This chapter does not deal with any specific perspectives or views, but with questions that arise when you implement your own perspectives and views. | ||

:*[[FAQ How do I create a new perspective?]] | :*[[FAQ How do I create a new perspective?]] | ||

| Line 278: | Line 293: | ||

=== Generic Editors === | === Generic Editors === | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Eclipse, editors are parts that have an associated input inside a workbench window and additional lifecycle methods, such as save and revert. This chapter answers questions about interacting with editors and about writing your own editors, whether they are text based or graphical. See Chapter 15 for a complete treatment of questions about writing your own text-based editors. | ||

:*[[FAQ What is the difference between a view and an editor?]] | :*[[FAQ What is the difference between a view and an editor?]] | ||

| Line 294: | Line 311: | ||

=== Actions, Commands, and Activities === | === Actions, Commands, and Activities === | ||

| + | |||

| + | This chapter answers questions about creating menu bars, context menus, and tool bars and the actions that fill them. A variety of both declarative and programmatic methods are available for contributing actions to the Eclipse UI and for managing and filtering those actions once they have been defined. This chapter also discusses the various ways to execute the long-running tasks that can be triggered by menu and toolbar actions. | ||

:*[[FAQ Actions, commands, operations, jobs: What does it all mean?]] | :*[[FAQ Actions, commands, operations, jobs: What does it all mean?]] | ||

| Line 321: | Line 340: | ||

=== Building Your Own Application === | === Building Your Own Application === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Prior to the introduction of RCP, most of the Eclipse community was focused on developing plug-ins for a particular Eclipse application called the workbench. Eclipse, however, has always supported the ability to create your own stand alone applications based on the Eclipse plug-in architecture. Eclipse applications can range from simple headless programs with no user interface to full-blown IDEs. In Eclipse 3.0, the platform began a shift toward giving greater power and flexibility to applications built on the Eclipse infrastructure. This chapter guides you through the process of building your own Eclipse application and explores some of the new Eclipse 3.0 APIs available only to applications. | ||

:*[[FAQ What is an Eclipse application?]] | :*[[FAQ What is an Eclipse application?]] | ||

| Line 339: | Line 360: | ||

=== Productizing an Eclipse Offering === | === Productizing an Eclipse Offering === | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this chapter, we look at turning an Eclipse configuration into a product. When an Eclipse product is created, the anonymous collection of plug-ins takes on application-specific branding, complete with custom images, splash screen, and launcher. In creating your own product, you typically also need to write an installer and uninstaller and consider how your users will obtain and upgrade your product. | ||

:*[[FAQ Where do I find suitable Eclipse logos and wordmarks?]] | :*[[FAQ Where do I find suitable Eclipse logos and wordmarks?]] | ||

| Line 356: | Line 379: | ||

=== Text Editors === | === Text Editors === | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

:*[[FAQ What support is there for creating custom text editors?]] | :*[[FAQ What support is there for creating custom text editors?]] | ||

Revision as of 21:36, 16 March 2006

The initial contents for these FAQ pages has come from The Offical Eclipse 3.0 FAQs written by John Arthorne and Chris Laffra.

Permission to publish the FAQ book contents here has been graciously offered by Addison-Wesley,

publishers of the official Eclipse Series

which wouldn't be possible without the great help from Greg Doench.

Contents

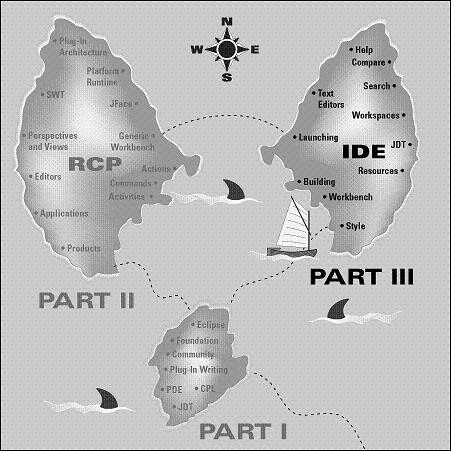

Part I -- The Eclipse Ecosystem

The Eclipse Community

Eclipse has taken the computing industry by storm. The download data for the Eclipse Software Development Kit (SDK) is astounding and a true ecosystem is forming around this new phenomenon. In this chapter we discuss what Eclipse is and who is involved in it and give you a glimpse of how large a community has put its weight behind this innovative technology.

An open source project would be nothing without a supporting community. The Eclipse ecosystem is a thriving one, with many research projects based on Eclipse, commercial products that ship on top of Eclipse, lively discussions in newsgroups and mailing lists, and a long list of articles and books that address the platform. The following pages will give you a roadmap of the community, so that you will feel more at home as you come to wander its winding streets.

- FAQ What is Eclipse?

- FAQ What is the Eclipse Platform?

- FAQ Where did Eclipse come from?

- FAQ What is the Eclipse Foundation?

- FAQ How can my users tell where Eclipse ends and a product starts?

- FAQ What are Eclipse projects and technologies?

- FAQ How do I propose my own project?

- FAQ Who is building commercial products based on Eclipse?

- FAQ What open source projects are based on Eclipse?

- FAQ What academic research projects are based on Eclipse?

- FAQ Who uses Eclipse in the classroom?

- FAQ What is an Eclipse Innovation Grant?

- FAQ What Eclipse newsgroups are available?

- FAQ How do I get access to Eclipse newsgroups?

- FAQ What Eclipse mailing lists are available?

- FAQ What articles on Eclipse have been written?

- FAQ What books have been written on Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I report a bug in Eclipse?

- FAQ How can I search the existing list of bugs in Eclipse?

- FAQ What do I do if my feature request is ignored?

- FAQ Can I get my documentation in PDF form, please?

- FAQ Where do I find documentation for a given extension point?

- FAQ How is Eclipse licensed?

Getting Started

Eclipse can be seen as a very advanced Java program. Running Eclipse may sound simple—simply run the included eclipse.exe or eclipse executable—yet in practice, you may want to tweak the inner workings of the platform. First, Eclipse does not come with a Java virtual machine (JVM), so you have to get one yourself. Note that Eclipse 3.0 needs a 1.4-compatible Java runtime environment (JRE).

To use Eclipse effectively, you will need to learn how to make Eclipse use a specific JRE. In addition, you may want to influence how much heap Eclipse may allocate, where it loads and saves its workspace from, and how you can add more plug-ins to your Eclipse installation.

This chapter should get you going. We also included some FAQs for plug-in developers who have already written plug-ins and want to get started with plug-in development for Eclipse 3.0.

- FAQ Where do I get and install Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I run Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I increase the heap size available to Eclipse?

- FAQ Where can I find that elusive .log file?

- FAQ Does Eclipse run on any Linux distribution?

- FAQ I unzipped Eclipse, but it won't start. Why?

- FAQ How do I upgrade Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I install new plug-ins?

- FAQ Can I install plug-ins outside the main install directory?

- FAQ How do I remove a plug-in?

- FAQ How do I find out what plug-ins have been installed?

- FAQ Where do I get help?

- FAQ How do I accommodate project layouts that don't fit the Eclipse model?

- FAQ What is new in Eclipse 3.0?

- FAQ Is Eclipse 3.0 going to break all of my old plug-ins?

- FAQ How do I prevent my plug-in from being broken when I update Eclipse?

Java Development in Eclipse

The topic of how to use Eclipse for typical Java development is beyond the scope of this FAQ list. We focus more on the issues Eclipse users may run into when developing new plug-ins for the platform. Also, as a plug-in developer, you need to be familiar with the ways in which Eclipse is used. To achieve seamless integration with the platform, your plug-in must respect common usage patterns and offer the same level of functionality that users of your plug-in have come to expect from the platform. This chapter focuses on user-level issues of interest to plug-in developers as users or as enablers for other users of the platform.

For a comprehensive guide to using Eclipse, refer to other books such as The Java Developer’s Guide to Eclipse (Addison-Wesley, 2003).

- FAQ How do I show/hide files like classpath in the Navigator?

- FAQ How do I link the Navigator with the currently active editor?

- FAQ How do I use the keyboard to traverse between editors?

- FAQ How can I rearrange Eclipse views and editors?

- FAQ Why doesn't my program start when I click the Run button?

- FAQ How do I turn off autobuilding of Java code?

- FAQ How do I hide referenced libraries in the Package Explorer?

- FAQ Where do my class files disappear to?

- FAQ What editor keyboard shortcuts are available?

- FAQ How do I stop the Java editor from showing a single method at once?

- FAQ How do I open a type in a Java editor?

- FAQ How do I control the Java formatter?

- FAQ How do I choose my own compiler?

- FAQ What Java refactoring support is available?

- FAQ How can Content Assist make me the fastest coder ever?

- FAQ How can templates make me the fastest coder ever?

- FAQ What is a Quick Fix?

- FAQ How do I profile my Java program?

- FAQ How do I debug my Java program?

- FAQ How do I find out the command-line arguments of a launched program?

- FAQ What is hot code replace?

- FAQ How do I set a conditional breakpoint?

- FAQ How do I find all Java methods that return a String?

- FAQ What can I view in the Hierarchy view?

- FAQ How do I add an extra library to my project's classpath?

- FAQ What is the advantage of sharing the project file in a repository?

- FAQ What is the function of the .cvsignore file?

- FAQ How do I set up a Java project to share in a repository?

- FAQ Why does the Eclipse compiler create a different serialVersionUID from javac?

Plug-In Development Environment

This book is all about extending the Eclipse Platform. The main instrument for extending the platform is a plug-in. Plug-ins solidify certain crucial design criteria underlying Eclipse. Special tooling has been developed as part of Eclipse to support the development of plug-ins. This set of plug-ins is called the Plug-in Development Environment; or PDE. The PDE tools cover the entire lifecycle of plug-in development, from creating them using special wizards to editing them to building them to launching them to exporting and sharing them.

This chapter describes the mechanics of plug-in development, such as creating plug-ins, features, and update sites, and introduces the PDE tooling. We go into much more depth about what plug-ins are in later FAQs. If you want to jump ahead, we suggest that you first visit FAQ What is a plug-in?.

- FAQ How do I create a plug-in?

- FAQ How do I use the plug-in Manifest Editor?

- FAQ Why doesn't my plug-in build correctly?

- FAQ How do I run my plug-in in another instance of Eclipse?

- FAQ What causes my plug-in to build but not to load in a runtime workbench?

- FAQ My runtime workbench runs, but my plug-in does not show. Why?

- FAQ How do I add images and other resources to a runtime JAR file?

- FAQ Can I add icons declared by my plugin.xml in the runtime JAR?

- FAQ When does PDE change a plug-in's Java build path?

- FAQ What is a PDE JUnit test?

- FAQ Where can I find the Eclipse plug-ins?

- FAQ How do I find a particular class from an Eclipse plug-in?

- FAQ Why do I get a 'plug-in was unable to load class' error when I activate a menu or toolbar action?

- FAQ What is the use of the build.xml file?

- FAQ How do I prevent my build.xml file from being overwritten?

- FAQ When is the build.xml script executed?

- FAQ How do I declare my own extension point?

- FAQ How do I find all the plug-ins that contribute to my extension point?

- FAQ Why is the interface for my new extension point not visible?

- FAQ Can my extension point schema contain nested elements?

- FAQ How do I create a feature?

- FAQ How do I synchronize versions between a feature and its plug-in(s)?

- FAQ What is the Update Manager?

- FAQ How do I create an update site (site.xml)?

- FAQ Why does my update site need a license?

Part II -- The Rich Client Platform

All about Plug-ins

Part I discussed the Eclipse ecosystem: how to run it, how to use it, and how to extend it. In this chapter, we revisit the topic of plug-ins and lay the groundwork for all plug-in development topics to be discussed in later chapters. This chapter answers questions about the core concepts of the Eclipse kernel, including plug-ins, extension points, fragments, and more. All APIs mentioned in this chapter are found in the org.eclipse.core.runtime plug-in.

- FAQ What is a plug-in?

- FAQ Do I use plugin or plug-in?

- FAQ What is the plug-in manifest file (plugin.xml)?

- FAQ How do I make my plug-in connect to other plug-ins?

- FAQ What are extensions and extension points?

- FAQ What is an extension point schema?

- FAQ How do I find out more about a certain extension point?

- FAQ When does a plug-in get started?

- FAQ Where do plug-ins store their state?

- FAQ How do I find out the install location of a plug-in?

- FAQ What is the classpath of a plug-in?

- FAQ How do I add a library to the classpath of a plug-in?

- FAQ How can I share a JAR among various plug-ins?

- FAQ How do I use the context class loader in Eclipse?

- FAQ Why doesn't Eclipse play well with Xerces?

- FAQ What is a plug-in fragment?

- FAQ Can fragments be used to patch a plug-in?

- FAQ What is a configuration?

- FAQ How do I find out whether the Eclipse Platform is running?

- FAQ Where does System.out and System.err output go?

- FAQ How do I locate the owner plug-in from a given class?

- FAQ How does OSGi and the new runtime affect me?

- FAQ What is a dynamic plug-in?

- FAQ How do I make my plug-in dynamic enabled?

- FAQ How do I make my plug-in dynamic aware?

Runtime Facilities

Above, we already discussed most of the basic functionality of the org.eclipse.core.runtime plug-in. This chapter covers the remaining facilities of Eclipse Platform runtime: APIs for logging, tracing, storing preferences, and other such core functionality. These various services, although not strictly needed by all plug-ins, are common enough that they merit being located directly alongside the Eclipse kernel. In Eclipse 3.0, this plug-in was expanded to add infrastructure for running and managing background operations. This chapter answers some of the questions that may arise when you start to use this new concurrency infrastructure.

- FAQ How do I use progress monitors?

- FAQ How do I use a SubProgressMonitor?

- FAQ How do I use the platform logging facility?

- FAQ How do I use the platform debug tracing facility?

- FAQ How do I load and save plug-in preferences?

- FAQ How do I use the preference service?

- FAQ What is a preference scope?

- FAQ How do I use IAdaptable and IAdapterFactory?

- FAQ Does the platform have support for concurrency?

- FAQ How do I prevent two jobs from running at the same time?

- FAQ What is the purpose of job families?

- FAQ How do I find out whether a particular job is running?

- FAQ How can I track the lifecycle of jobs?

- FAQ How do I create a repeating background task?

Standard Widget Toolkit (SWT)

One of the great success stories of the Eclipse Platform has been the overwhelming groundswell of support for its windowing toolkit, SWT. This toolkit offers a fast, thin, mostly native alternative to the most common Java UI toolkits, Swing and Abstract Windowing Toolkit (AWT). Religious debates abound over the relative merits of Swing versus SWT, and we take great pains to avoid these debates here. Suffice it to say that SWT generates massive interest and manages to garner as much, if not more, interest as the Eclipse Platform built on top of it.

The popularity of SWT has forced us to take a slightly different approach with this chapter. The SWT newsgroup was created in July 2003 and since then has generated an average of 136 messages every day. In this book, we could not even scratch the surface of the information available there. Although we could present the illusion of completeness by answering a couple dozen popular technical questions, we would not be doing the topic justice. Instead, we focus on answering a few of the higher-level questions and providing as many forward pointers as we can to further information on SWT available elsewhere. A benefit of SWT’s popularity is the wealth of Web sites, discussion forums, books, and other forms of documentation out there. Thus, although we won’t be able to answer all SWT questions, we hope at least to steer you to the resources that can. However, a handful of questions are asked so often that we can’t resist answering them here.

- FAQ What is SWT?

- FAQ Why does Eclipse use SWT?

- FAQ Can I use SWT outside Eclipse for my own project?

- FAQ Are there any visual composition editors available for SWT?

- FAQ Why do I have to dispose of colors, fonts, and images?

- FAQ Why do I get an invalid thread access exception?

- FAQ How do I get a Display instance?

- FAQ How do I prompt the user to select a file or a directory?

- FAQ How do I display a Web page in SWT?

- FAQ How do I embed AWT and Swing inside SWT?

- FAQ Where can I find more information on SWT?

JFace

JFace is a Java application framework based on SWT. The goal of JFace is to provide a set of reusable components that make it easier to write a Java-based GUI application. Among the components JFace provides are such familiar GUI concepts as wizards, preference pages, actions, and dialogs. These components tend to be the bits and pieces that are integral to the basic widget set but are common enough that there is significant benefit to drawing them together into a reusable framework. Although its heritage is based on a long line of frameworks for writing IDEs, most of JFace is generally useful in a broad range of graphical desktop applications. JFace has a few connections to classes in the Eclipse runtime kernel, but it is fairly straightforward to extract JFace and SWT for use in stand-alone Java applications that are not based on the Eclipse runtime. JFace does not make use of such Eclipse-specific concepts as extensions and extension points.

- FAQ What is a viewer?

- FAQ What are content and label providers?

- FAQ What kinds of viewers does JFace provide?

- FAQ Why should I use a viewer?

- FAQ How do I sort the contents of a viewer?

- FAQ How do I filter the contents of a viewer?

- FAQ How do I use properties to optimize a viewer?

- FAQ What is a label decorator?

- FAQ How do I use image and font registries?

- FAQ What is a wizard?

- FAQ How do I specify the order of pages in a wizard?

- FAQ How can I reuse wizard pages in more than one wizard?

- FAQ Can I reuse wizards from other plug-ins?

- FAQ How do I make my wizard appear in the UI?

- FAQ How do I run a lengthy process in a wizard?

- FAQ How do I launch the preference page that belongs to my plug-in?

- FAQ How do I ask a simple yes or no question?

- FAQ How do I inform the user of a problem?

- FAQ How do I create a dialog with a details area?

- FAQ How do I set the title of a custom dialog?

- FAQ How do I save settings for a dialog or wizard?

Generic Workbench

This chapter covers FAQs relating to the generic workbench and its APIs. Workbench is the term used for the generic Eclipse UI. Originally the UI was called the desktop, but because Eclipse was a platform primarily for tools rather than for stationery, workbench was deemed more suitable. In Eclipse 3.0, tools are no longer the sole focus, so the term Rich Client Platform, is starting to creep in as the term for the generic, non-tool-specific UI. After all, people don’t want to play mine sweeper or send e-mails to Mom from such a prosaically named application as a workbench. A rich client, on the other hand, is always welcome at the dinner table.

Many of the important workbench concepts, such as editors, views, and actions, generate enough questions that they deserve their own chapters. This chapter focuses on general questions about integrating your plug-in with the various extension hooks the workbench provides.

- FAQ Pages, parts, sites, windows: What is all this stuff?

- FAQ How do I find out what object is selected?

- FAQ How do I find out what view or editor is selected?

- FAQ How do I find the active workbench page?

- FAQ How do I show progress on the workbench status line?

- FAQ Why should I use the new progress service?

- FAQ How do I write a message to the workbench status line?

- FAQ How do I create a label decorator declaratively?

- FAQ How do I add label decorations to my viewer?

- FAQ How do I make the workbench shutdown?

- FAQ How can I use IWorkbenchAdapter to display my model elements?

- FAQ How do I create my own preference page?

- FAQ How do I use property pages?

- FAQ How do I open a Property dialog?

- FAQ How do I add my wizard to the New, Import, or Export menu categories?

- FAQ Can I activate my plug-in when the workbench starts?

- FAQ How do I create an image registry for my plug-in?

- FAQ How do I use images defined by other plug-ins?

- FAQ How do I show progress for things happening in the background?

- FAQ How do I switch from using a Progress dialog to the Progress view?

- FAQ Can I make a job run in the UI thread?

- FAQ Are there any special Eclipse UI guidelines?

- FAQ Why do the names of some interfaces end with the digit 2?

Perspectives and Views

This chapter answers questions about two central concepts in the Eclipse Platform UI. Perspectives define the set of actions and parts that appear in a workbench window and specify the initial size and position of views within that window. Views are the draggable parts that make up the bulk of a workbench window’s contents. This chapter does not deal with any specific perspectives or views, but with questions that arise when you implement your own perspectives and views.

- FAQ How do I create a new perspective?

- FAQ How can I add my views and actions to an existing perspective?

- FAQ How do I show a given perspective?

- FAQ What is the difference between a perspective and a workbench page?

- FAQ How do I create fixed views and perspectives?

- FAQ What is a view?

- FAQ What is the difference between a view and a viewer?

- FAQ How do I create my own view?

- FAQ How do I set the size or position of my view?

- FAQ Why can't I control when, where, and how my view is presented?

- FAQ How will my view show up in the Show View menu?

- FAQ How do I make my view appear in the Show In menu?

- FAQ How do I add actions to a view's menu and toolbar?

- FAQ How do I make a view respond to selection changes in another view?

- FAQ How does a view persist its state between sessions?

- FAQ How do I open multiple instances of the same view?

Generic Editors

In Eclipse, editors are parts that have an associated input inside a workbench window and additional lifecycle methods, such as save and revert. This chapter answers questions about interacting with editors and about writing your own editors, whether they are text based or graphical. See Chapter 15 for a complete treatment of questions about writing your own text-based editors.

- FAQ What is the difference between a view and an editor?

- FAQ How do I open an editor programmatically?

- FAQ How do I open an external editor?

- FAQ How do I dynamically register an editor to handle a given extension?

- FAQ How do I switch to vi or emacs-style key bindings?

- FAQ How do I create my own editor?

- FAQ How do I enable the Save and Revert actions?

- FAQ How do I enable global actions such as Cut, Paste, and Print in my editor?

- FAQ How do I hook my editor to the Back and Forward buttons?

- FAQ How do I create a form-based editor, such as the plug-in Manifest Editor?

- FAQ How do I create a graphical editor?

- FAQ How do I make an editor that contains another editor?

Actions, Commands, and Activities

This chapter answers questions about creating menu bars, context menus, and tool bars and the actions that fill them. A variety of both declarative and programmatic methods are available for contributing actions to the Eclipse UI and for managing and filtering those actions once they have been defined. This chapter also discusses the various ways to execute the long-running tasks that can be triggered by menu and toolbar actions.

- FAQ Actions, commands, operations, jobs: What does it all mean?

- FAQ What is an action set?

- FAQ How do I make my action set visible?

- FAQ How do I add actions to the global toolbar?

- FAQ How do I add menus to the main menu?

- FAQ How do I add actions to the main menu?

- FAQ Why are some actions activated without a target?

- FAQ Where can I find a list of existing action group names?

- FAQ What is the difference between a command and an action?

- FAQ How do I associate an action with a command?

- FAQ How do I create my own key-binding configuration?

- FAQ How do I provide a keyboard shortcut for my action?

- FAQ How can I change the name or tooltip of my action?

- FAQ How do I hook into global actions, such as Copy and Delete?

- FAQ How do I build menus and toolbars programmatically?

- FAQ How do I make menus with dynamic contents?

- FAQ What is the difference between a toolbar and a cool bar?

- FAQ Can other plug-ins add actions to my part's context menu?

- FAQ How do I add other plug-ins' actions to my menus?

- FAQ What is the purpose of activities?

- FAQ How do I add activities to my plug-in?

- FAQ How do activities get enabled?

- FAQ What is the difference between perspectives and activities?

Building Your Own Application

Prior to the introduction of RCP, most of the Eclipse community was focused on developing plug-ins for a particular Eclipse application called the workbench. Eclipse, however, has always supported the ability to create your own stand alone applications based on the Eclipse plug-in architecture. Eclipse applications can range from simple headless programs with no user interface to full-blown IDEs. In Eclipse 3.0, the platform began a shift toward giving greater power and flexibility to applications built on the Eclipse infrastructure. This chapter guides you through the process of building your own Eclipse application and explores some of the new Eclipse 3.0 APIs available only to applications.

- FAQ What is an Eclipse application?

- FAQ How do I create an application?

- FAQ What is the minimal Eclipse configuration?

- FAQ How do I create a Rich Client application?

- FAQ How do I customize the menus in an RCP application?

- FAQ How do I make key bindings work in an RCP application?

- FAQ Can I create an application that doesn't have views or editors?

- FAQ How do I specify where application data is stored?

- FAQ Can I create an application that doesn't have a data location?

- FAQ What is an Eclipse product?

- FAQ What is the difference between a product and an application?

- FAQ How do I distribute my Eclipse offering?

- FAQ Can I use an installation program to distribute my Eclipse product?

- FAQ Can I install my product as an add-on to another product?

Productizing an Eclipse Offering

In this chapter, we look at turning an Eclipse configuration into a product. When an Eclipse product is created, the anonymous collection of plug-ins takes on application-specific branding, complete with custom images, splash screen, and launcher. In creating your own product, you typically also need to write an installer and uninstaller and consider how your users will obtain and upgrade your product.

- FAQ Where do I find suitable Eclipse logos and wordmarks?

- FAQ When do I need to write a plug-in install handler?

- FAQ How do I support multiple natural languages in my plug-in messages?

- FAQ How do I replace the Eclipse workbench window icon with my own?

- FAQ How do I write my own eclipseexe platform launcher?

- FAQ Who shows the Eclipse splash screen?

- FAQ How can I publish partial upgrades (patches) to my product?

Part III -- The Eclipse IDE Platform

Text Editors

- FAQ What support is there for creating custom text editors?

- FAQ I'm still confused! How do all the editor pieces fit together?

- FAQ How do I get started with creating a custom text editor?

- FAQ How do I use the text document model?

- FAQ What is a document partition?

- FAQ How do I add Content Assist to my editor?

- FAQ How do I provide syntax coloring in an editor?

- FAQ How do I support formatting in my editor?

- FAQ How do I insert text in the active text editor?

- FAQ What is the difference between highlight range and selection?

- FAQ How do I change the selection on a double-click in my editor?

- FAQ How do I use a model reconciler?

Help, Search, and Compare

- FAQ How do I add help content to my plug-in?

- FAQ How do I provide F1 help?

- FAQ How do I contribute help contexts?

- FAQ How can I generate HTML and toc.xml files?

- FAQ How do I write a Search dialog?

- FAQ How do I implement a search operation?

- FAQ How do I display search results?

- FAQ How can I use and extend the compare infrastructure?

- FAQ How do I create a Compare dialog?

- FAQ How do I create a compare editor?

Workspace and Resources API

- FAQ How are resources created?

- FAQ Can I create resources that don't reside in the file system?

- FAQ What is the difference between a path and a location?

- FAQ When should I use refreshLocal?

- FAQ How do I create my own tasks, problems, bookmarks, and so on?

- FAQ How can I be notified of changes to the workspace?

- FAQ How do I prevent builds between multiple changes to the workspace?

- FAQ Why should I add my own project nature?

- FAQ Where can I find information about writing builders?

- FAQ How do I store extra properties on a resource?

- FAQ How can I be notified on property changes on a resource?

- FAQ How and when do I save the workspace?

- FAQ How can I be notified when the workspace is being saved?

- FAQ Where is the workspace local history stored?

- FAQ How can I repair a workspace that is broken?

- FAQ What support does the workspace have for team tools?

Workbench IDE

- FAQ How do I open an editor on a file in the workspace?

- FAQ How do I open an editor on a file outside the workspace?

- FAQ How do I open an editor on something that is not a file?

- FAQ Why don't my markers show up in the Tasks view?

- FAQ Why don't my markers appear in the editor's vertical ruler?

- FAQ How do I access the active project?

- FAQ What are IWorkspaceRunnable, IRunnableWithProgress, and WorkspaceModifyOperation?

- FAQ How do I write to the console from a plug-in?

- FAQ How do I prompt the user to select a resource?

- FAQ Can I use the actions from the Navigator in my own plug-in?

- FAQ What APIs exist for integrating repository clients into Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I deploy projects to a server and keep the two synchronized?

- FAQ What is the difference between a repository provider and a team subscriber?

- FAQ What is a launch configuration?

- FAQ When do I use a launch delegate?

- FAQ What is Ant?

- FAQ Why can't my Ant build find javac?

- FAQ How do I add my own external tools?

- FAQ How do I create an external tool builder?

Implementing Support for Your Own Language

- FAQ What is eScript?

- FAQ Language integration phase 1: How do I compile and build programs?

- FAQ How do I load source files edited outside Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I run an external builder on my source files?

- FAQ How do I implement a compiler that runs inside Eclipse?

- FAQ How do I react to changes in source files?

- FAQ How do I implement an Eclipse builder?

- FAQ Where are project build specifications stored?

- FAQ How do I add a builder to a given project?

- FAQ How do I implement an incremental project builder?

- FAQ How do I handle setup problems for a given builder?

- FAQ How do I make my compiler incremental?

- FAQ Language integration phase 2: How do I implement a DOM?

- FAQ How do I implement a DOM for my language?

- FAQ How can I ensure that my model is scalable?

- FAQ Language integration phase 3: How do I edit programs?

- FAQ How do I write an editor for my own language?

- FAQ How do I add Content Assist to my language editor?

- FAQ How do I add hover support to my text editor?

- FAQ How do I create problem markers for my compiler?

- FAQ How do I implement Quick Fixes for my own language?

- FAQ How do I support refactoring for my own language?

- FAQ How do I create an Outline view for my own language editor?

- FAQ Language integration phase 4: What are the finishing touches?

- FAQ What wizards do I define for my own language?

- FAQ When does my language need its own nature?

- FAQ When does my language need its own perspective?

- FAQ How do I add documentation and help for my own language?

- FAQ How do I support source-level debugging for my own language?

Java Development Tool API

- FAQ How do I extend the JDT?

- FAQ What is the Java model?

- FAQ How do I create Java elements?

- FAQ How do I create a Java project?

- FAQ How do I manipulate Java code?

- FAQ What is a working copy?

- FAQ What is a JDOM?

- FAQ What is an AST?

- FAQ How do I create and examine an AST?

- FAQ How do I distinguish between internal and external JARs on the build path?

- FAQ How do I launch a Java program?

- FAQ What is JUnit?

- FAQ How do I participate in a refactoring?

- FAQ What is LTK?