Notice: this Wiki will be going read only early in 2024 and edits will no longer be possible. Please see: https://gitlab.eclipse.org/eclipsefdn/helpdesk/-/wikis/Wiki-shutdown-plan for the plan.

EMF Compare/Logical Model

Contents

Logical Model

What is a logical model?

We name "logical model" a set of physical resources that form a coherent business-related model. For example, we could say that a given Java class forms a coherent logical model only when it is linked with all of its imported classes.

In the case of EMF, we name a logical resource (or model) the EMF resource loaded in memory, as opposed to a physical resource (or file) that is merely the serialization of this model on disk. A given EMF model can reference a number of other models, and it will be incoherent, or even sometimes corrupted, if these other models are not loaded in memory. In EMF, a given model can be serialized as a single file, fragmented in multiple files on disk, or reference multiple files. The logical model is only coherent when the whole set of its physical files is accessible.

Eclipse Team

The Eclipse Team project (referred as "Team" in this document) provides an API named "model providers". This API allows implementers to define the semantics of what is a "logical model" in his case. In short, it allows us to link any number of physical resources to a given "starting" file.

Technically, this is done through an extension point that can be implemented by anyone and that will adapt a file (a workspace IResource) to a set of files (a Team ResourceTraversal). The model providers can be queried by anyone who calls actions on workspace files in order to determine if this action can be done against a single file or if it should be executed against a set of files.

Limitations

Team only provides the API to define logical models. It is then the responsibility of its clients to properly query the model provider when calling an action. In the context of EMF Compare, we are interested in the "compare" actions. These actions are contributed by the repository providers (CVS, EGit, Subversive, Subclipse, Clearcase...). It is their responsibility, within the code of these actions, to query the model providers in order to determine if the selected files can be compared alone... or if they need to be compared along with a set of others.

- The CVS plugin does not consistently use it. For example, when using "compare with > latest from HEAD" on a file that is part of a logical model, it will 'see' the logical model and open the "synchronize" perspective instead of a compare editor : this is what's expected. However, when the user, from the synchronization view, asks to see the differences (right-click then select 'open in compare editor')... CVS will not query the logical model, comparing the file alone (see also bug 345415).

- The EGit, Subversive and Subclipse plugins never query the model providers for any comparison action.

EMF Compare

In the case of EMF Compare, the above limitations were a show-stopper. EMF models cannot simply be reduced to single files as that would totally break their consistency when trying to compare them.

Chosen solution

EMF Compare now uses its own implementation aiming at this same goal, that we named synchronization model. In short, instead of expecting the repository providers to query the model providers, EMF Compare will take the file (or set of files) that it is fed and expand it to the full logical model by querying the synchronization model.

This custom implementation also allows us to not only resolve the whole logical model of a given physical file, but also to determine which parts of this model should be included in the comparison scope. Indeed, under the semantics of EMF, if we can determine that two physical files are binary identical in their two distinct revisions, then we also know that the part of the logical model they represent are identical themselves. There would be no need to compare them. This allows to save both time and memory, killing two birds with one stone.

How it works

When the user selects a file A in his workspace and asks to compare it with a remote revision (for example, the "latest from HEAD"), the repository provider (CVS in this case) fetches the remote content of A in the selected revision (we'll call it A'). Once the remote revision fetched, the repository provider considers his work finished and feeds EMF Compare the two files (A and A') and lets it begin his own work. This is fine and dandy when the logical model of A only spans a single file ... but if A references another file B, then the comparison will not be coherent as EMF Compare operates on the logical model, not on its serialized form.

Thus, EMF Compare will not immediately launch the comparison of the files it is fed. Before any further work, it will query the synchronization model with these files in order to expand them to their whole logical model.

- In the case of a local file (A), it will load it as an EMF Resource and resolve all of its cross references. During the resolution process, we'll be able to track all of the "other" files required by the "starting point" A. In the example above, we'll end up with a set containing both A and B.

- In the case of a remote file (A'), it will try and load the streamed revision of the resource, then query the repository provider for the other files needed by A' in the correct revision. A revision is deemed "correct" if it precedes (or is equal to) the revision of A' that we have initially been fed. This will lead us to a set containing A' and B'.

Once the full logical model is resolved, EMF Compare can properly do the comparison work. Since we know of all fiels that compose our model, we'll also be able to safely merge differences without compromising the coherence of the whole.

However, even if we can launch EMF Compare at this point, the synchronization model also offers us one more possibility. EMF models can span thousands of physical files sometimes amounting to such a huge number of elements that it would not fit into the machine's memory if we tried to load it as a whole. The synchronization model knows how to retrieve the content of all of these files; it can also be used to minimize the set to only those which really did change. Indeed, we consider that files that are binary identical wield yield fragments of the logical model that will also be strictly identical. By removing these "identical" fragments, we can drastically limit the size of the logical model we'll load into memory, compacting it to a size that will fit before we launch the comparison on the remaining fragments.

In other words, the synchronization model allows us to compare models with a time and memory cost that is relative to the size of the actual changeset instead of having it depend on the input models size.

Example

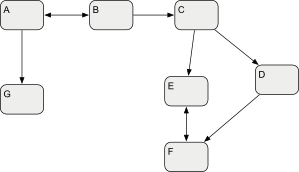

Let's consider the following sample :

| Origin |

|---|

| Left | Right |

|---|---|

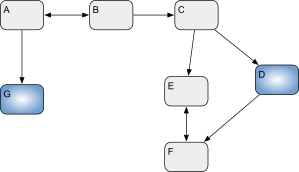

Each of the three sides is an EMF model composed of 20 fragments. Origin is the common ancestor of left and right. The orange-colored fragments are those that actually present differences (so D and G have been modified in the "left" copy while A, E, G and P have been modified in the "right" copy).

In order to compare these three models together, we would normally need to load all 60 fragments in memory. However, with the help of the synchronization model we can narrow it down to the modified fragments only. What we'll really load, then, are the following fragments for each three sides :

In other words, we are actually only loading 15 fragments out of the initial 60. This amounts to 75% less memory usage if we consider all fragments to be of equal "weight". And this is only for small models; the ratio of saved memory really going up for extremely large models. Of course, all of these objects that we are not loading in memory are all objects that we no longer need to compare, bringing an incredible performance boost along with the memory gain.

Some numbers

When we got EMF Compare 1.3 out, we did some performance snapshots of what we had on some UML models with known counts of elements. Here were the specifications of the structure of the three test models. "fragments" are the number of fragmented files, the rest are the UML elements contained by the samples (spread out within the fragments) :

| Small | Nominal | Large | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragments | 99 | 399 | 947 |

| Packages | 97 | 389 | 880 |

| Classes | 140 | 578 | 2169 |

| Primitive Types | 581 | 5370 | 17152 |

| Data Types | 599 | 5781 | 18637 |

| State Machines | 55 | 209 | 1311 |

| States | 202 | 765 | 10156 |

| Dependencies | 235 | 2522 | 8681 |

| Transitions | 798 | 3106 | 49805 |

| Operations | 1183 | 5903 | 46029 |

| Total element count | 3890 | 24623 | 154820 |

Time and memory used required to compare each of the model sizes (the model is copied, randomly modified, then the copy is compared with its original).

EMF Compare 1.3

Note that these were "CPU time" measures : we used a Java profiler to measure the duration of the comparison process, without regard to the actual wall time : we measured the time that the CPU was active during this process. As EMF Compare 1 was not multi-threaded, this means that these figures are slightly lower than the time actually perceived by the user for the same action. (See Wall Time and System Time on wikipedia.)

| Small | Nominal | Large | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (seconds) | 6 | 22 | 125 |

| Maximum Heap (MB) | 555 | 1019 | 2100 |

This meant that the memory management of EMF Compare was really limiting as soon as we were dealing with large models (more than 2GB of heap space needed to load models that "weigh" 50 MB on disk). Furthermore, the main time sink was the differencing process, and that could also be narrowed down to the fact that there were plainly too many object to compare : for two-way comparisons, we were loading the model twice, for three-way comparisons, three instances of the model were loaded in memory. Not only that, but we were iterating twice on all models (one for matching, one for differencing).

The full report can be downloaded from here.

EMF Compare 2.1

Note that these are "wall time" measures : we used a stopwatch to time the duration of the comparison, from a click on the "compare with > each other" action to the opening of the comparison editor.

| Small | Nominal | Large | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (seconds) | 5 | 13 | 48 |

| Maximum Heap (MB) | 262 | 318 | 422 |

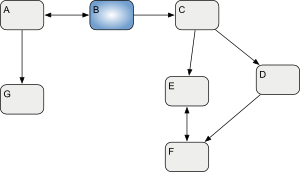

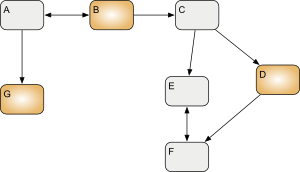

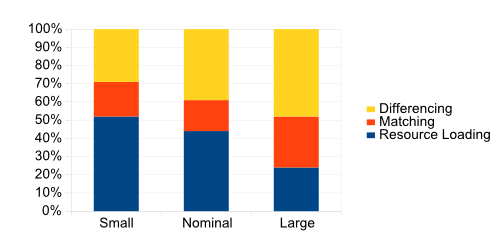

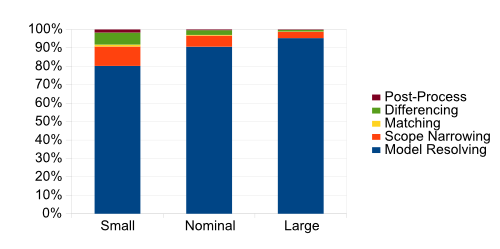

These figures can be broken down in 5 main phases :

- Model Resolving : From a given "starting point" (in the example above, fragment A), finding all other fragments required for the comparison of the whole logical model.

- Scope Narrowing : From the set of fragments composing the logical model, finding those that actually can present differences (A, D, E, G and P in the above example), then loading these fragments in memory.

- Matching : Iterating over the two (or three) loaded logical models in order to map elements together two-by-two (or three-by-three).

- Differencing : The matching phase told us which elements were matching together (Class C1 in the left logical model with Class C1' in the right logical model for example). The differencing phase will try and determine whether those two elements are equal or if they present differences (for example, the name of the class changed from C1 to C1')

- Post-processing : Now that we know all differences between the models, we still need to determine equivalences -two differences that represent the same change (for example, differences on opposite references)-, requirements -a difference depends on another (for example, the addition of a class C1 in package P1 depends on the addition of package P1)-, conflicts -a conflictual change has been made in the left and right models as compared to the origin...

Okay, this graph does not leave much to interpretation. The model resolving time totally dwarfs the other comparison phases. That was actually our aim for EMF Compare 2 : model resolving represents the bulk of the I/O operations of EMF Compare, and we aimed at reducing the actual comparison to the utmost minimum time. So not only are we greatly improving the memory cost (only 400MB of heap space to compare something that required more than 2GB with EMF Compare 1), but we also reduced the comparison time (and the scalability) to a great extent.

Limitations

The use of our own implementation effectively allows us to bypass some of the aforementioned limitations since we no longer rely on the repository providers in our specific case.

However, if we can enforce the coherence of the models during the comparison, this approach still does not take into account the other aspects of collaboration with models. Even if comparing and merging two linked models is fine, it is still the repository provider's responsibility to query Team's model providers in order to "commit", "push", or even "replace" the models as a whole instead of acting on single physical files. Thus, most of the limitations mentioned above still hold, though we fixed those that applied to comparison actions.

Improvement Axes

As shown with the above graphs